|

Expansion of Hong Kong International Airport into a Three-Runway System |

|

|

|

|

|

Marine Travel Routes and Management Plan for High Speed Ferries of SkyPier |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Chapter Title

Figure

1‑1 Key Traffic Routes for Future Traffic Environment 2

Figure

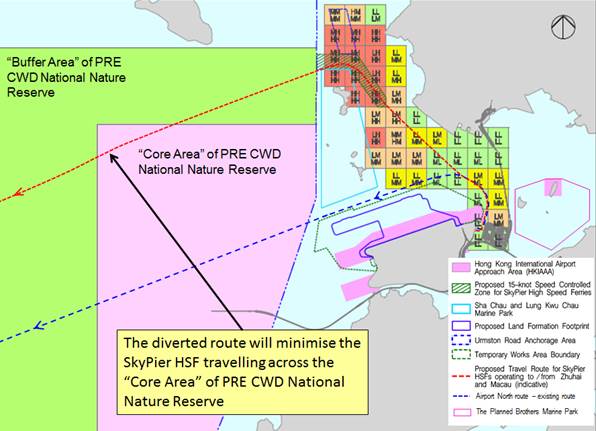

2‑3 Recommended Route Diversion and the PRE CWD

National Nature Reserve_ 8

Figure

3‑1 Various Marine Constraints in the North Lantau Waters 10

Figure 3‑2 Existing Marine

Traffic Plan (BMT, 2014) 12

Figure

3‑3 Pre-defined Marine Travel Route for SkyPier HSFs operating to / from

Zhuhai and Macau_ 13

Figure

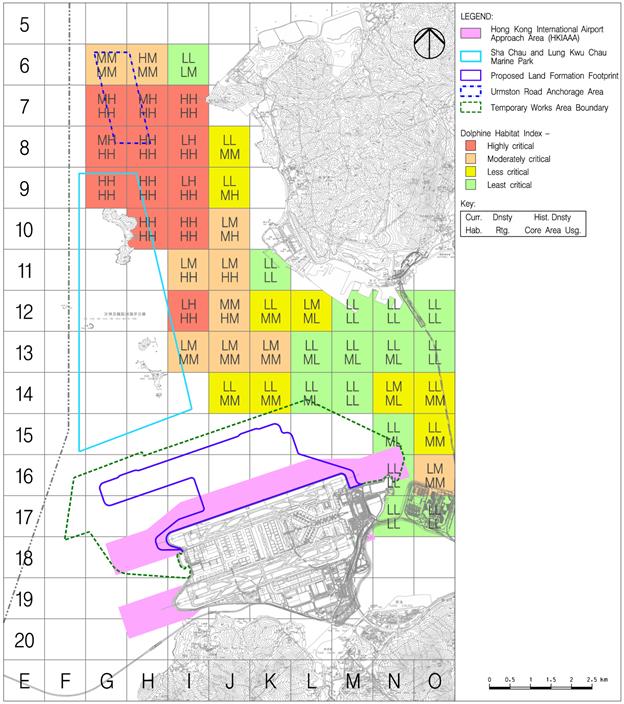

3‑8 Dolphin Habitat Index Developed for this Plan_ 19

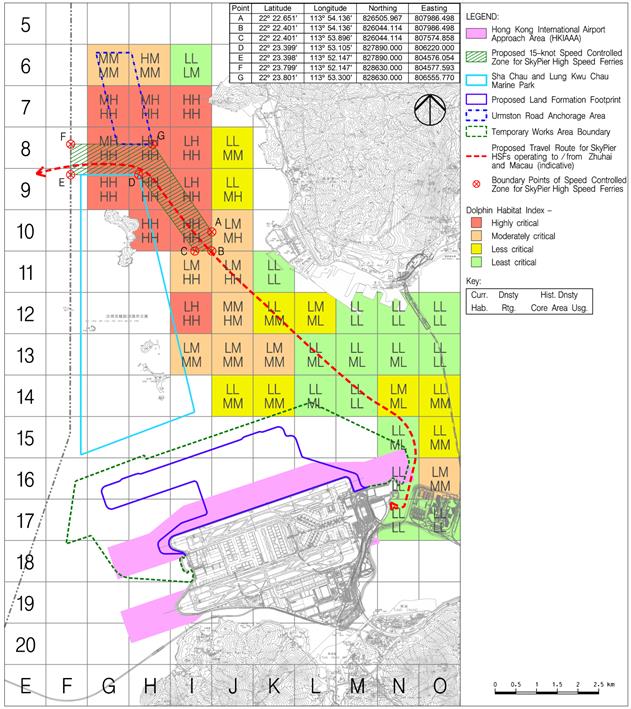

Figure

3‑9 Speed Controlled Zone for SkyPier HSFs 20

Figure

3‑10 Density of Chinese white dolphins from HZMB-HKLR Monitoring Reports 21

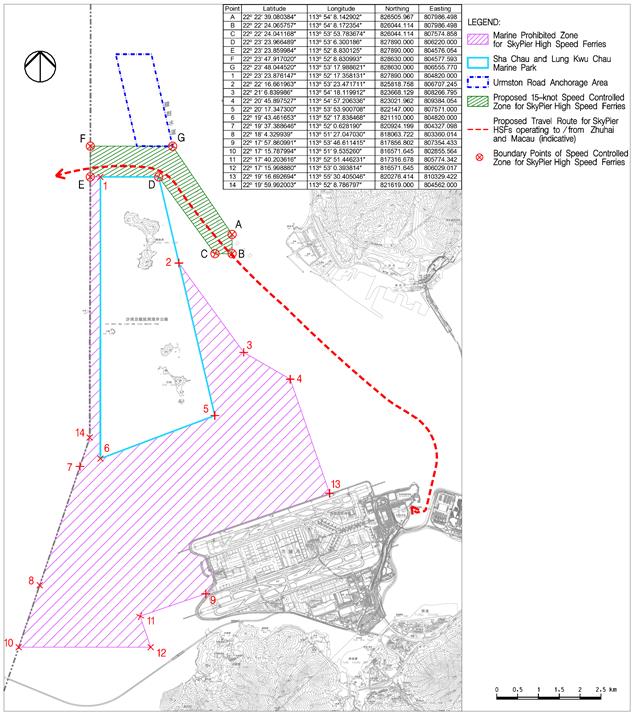

Figure

3‑11 Marine Prohibited Zone for SkyPier HSFs 24

Figure 3‑12 EIA Forecast of Daily Average SkyPier HSFs in 2021 and 2030_ 25

Table

Table 2-1 Summary of

HSF impacts on CWDs (excerpt from Table 13-29 of the EIA Report)

Table 2-2 Speed of High

Speed Ferry and the Corresponding Sound Pressure Level

Government of the Hong Kong Special

Administrative Region (HKSAR) approved in principle the adoption of the

Three-Runway System (3RS) as the future development option for Hong Kong

International Airport (HKIA) for planning purposes on 20 March 2012, and also

approved the recommendation of Airport Authority Hong Kong (AAHK) to proceed

with the statutory environmental impact assessment (EIA). An EIA study brief

(ESB-250/2012) for the 3RS project (henceforth referred to as the ‘project’)

was issued by the Environmental Protection Department (EPD) on 10 August 2012.

The EIA report has been prepared according to the EIA study brief requirements,

which identified 12 key environmental assessment aspects to be addressed as

part of the EIA study. On 7 November

2014, the EIA for the project (EIA Register No.: AEIAR-185/2014) was approved

and an Environmental Permit (EP) (Permit No.: EP-489/2014) was issued for the

project.

The project is proposed to be located on a

new land formation immediately north of HKIA in North Lantau, covering a

permanent footprint of approximately 650 ha. As stated in the approved EIA, the

project primarily comprises:

§ New third runway with associated taxiways, aprons and aircraft stands;

§ New passenger concourse building;

§ Expansion of the existing Terminal 2 (T2) building; and

§ Related airside and landside works, and associated ancillary and supporting facilities.

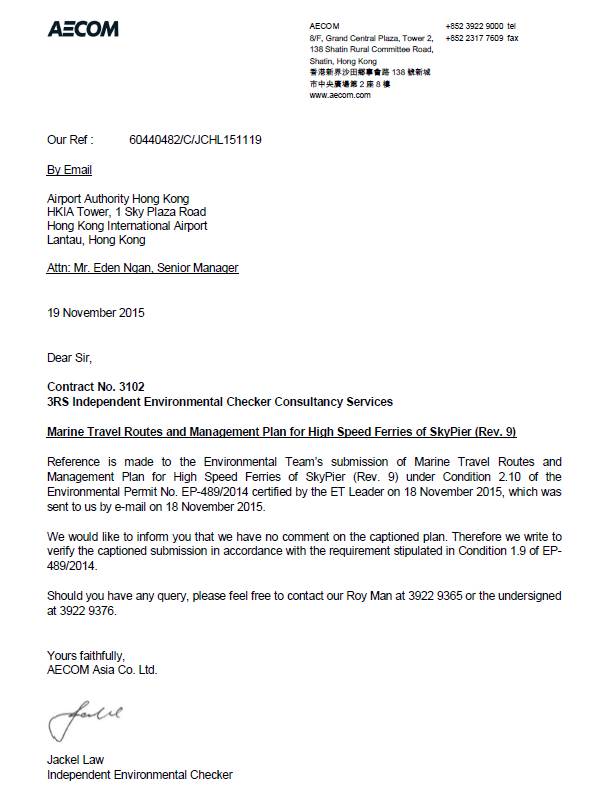

The area around HKIA is well used by a variety of

vessel types, of which High Speed Ferries (HSFs) pose the most significant

collision threat to Chinese White Dolphins (CWDs) and are also known to

generate the loudest underwater noise. During the 3RS land formation, works

area will be designated and demarcated by floating booms and as the land for

the 3RS new platform is formed, the navigation routes for these vessels will be

constrained to within a narrower area just north of the new Hong Kong

International Airport Approach Area (HKIAAA; Figure

1‑1),

although no change to the direction of traffic flows are expected, these continuing

to comprise two-way transits east and west.

Figure

1‑1

Key Traffic Routes for Future Traffic Environment

In accordance with Clause 2.10 of the EP,

the permit holder shall submit a Marine Travel Routes and Management Plan (The

Plan) for high speed ferries (HSF) of the SkyPier.

The Plan shall include at least the following information/specifications:

i. The imposition of a speed limit within Hong Kong waters which are hotspots of the CWD during the construction phase so as to minimize chances of collision and disturbance to the CWD;

ii. To cap the number of SkyPier HSF at the current level of operation (i.e. an annual daily average of 99) prior to designation of the proposed marine park; and

iii. Explore the feasibility of imposing a daily cap on the number of HSF leaving the SkyPier and imposing further speed restriction at different spots along the marine routes after detailed study.

This Plan has been prepared to detail the

information/specifications listed above to fulfil the EP requirement Clause

2.10.

SkyPier, which is located at north-east of Hong Kong

International Airport (HKIA), provides HSF service for transfer passengers to

eight ports in Pearl River Delta (PRD) and Macao include Dongguan Humen, Guangzhou Nansha, Macao

Maritime Ferry Terminal, Macao Taipa, Shenzhen Fuyong, Shenzhen Shekou, Zhongshan and

Zhuhai Jiuzhou. The draft of SkyPier

HSFs travelling in the waters north of Lantau Island is approximately 1 – 2 m.

This plan focuses on those SkyPier HSFs traveling to

/ from Macau and Zhuhai as the route for these services passes through waters

between the Hong Kong International Airport Approach Area (HKIAAA) and the Sha

Chau and Lung Kwu Chau Marine Park (SCLKCMP), which

is identified in the approved EIA report as an important travelling area for

CWDs requiring the development of mitigation measures at both the construction

and operation phases of the 3RS project in order to reduce identified impacts

to an acceptable level..

Photo 2-1 Photo of High Speed

Ferry

The approved EIA Report including the literature

review and the project specific dolphin survey findings have identified that

the waters to the north of the existing airport are an important travelling

area for CWDs, noting that CWDs use this area mainly for moving between the

main feeding areas or known areas of higher CWD abundance around the Brothers,

in west Lantau and around Sha Chau and Lung Kwu Chau.

The approved EIA assessed the indirect impacts of HSFs currently navigating in the waters between the Hong Kong International Airport Approach Area and the SCLKCMP on CWDs (i.e. the CWD travelling area) at both the construction and operational phases. Identified impacts included increased acoustic disturbance, changes to CWD movement patterns, and increased risk of injury/mortality associated with marine traffic were assessed in the EIA and are summarized in Table 2‑1 below (extracted from Table 13-29 of the EIA Report.

Table 2‑1 Summary of HSF impacts on CWDs

(excerpt from Table 13-29 of the EIA Report)

|

Potential Impact |

Source |

Receiver |

Significance of

Impact |

Further Mitigation

/ Enhancement Required |

|

Construction Phase |

||||

|

Increased acoustic disturbance from changes to

marine vessels and ferry traffic |

HSF |

CWD |

Moderate |

Yes |

|

Changes to CWD movement patterns as a result of

marine traffic |

HSF |

CWD |

Moderate |

Yes |

|

Increased risk of injury/ mortality to CWDs from

marine traffic |

HSF |

CWD |

High |

Yes |

|

Operational Phase |

||||

|

Increased acoustic disturbance from increased marine

traffic |

HSF |

CWD |

Moderate-high |

Yes |

|

Changes to CWD movement patterns from marine traffic |

HSF |

CWD |

Moderate-high |

Yes |

|

Increased

risk of injury/ mortality |

HSF |

CWD |

High |

Yes |

The EIA for 3RS described that the HSFs utilising the SkyPier would move up to full speed of 30 - 40 knots in 1-1.5 km after leaving the pier and would slow down within approx. 1 km of approaching the pier. The HSFs would move at high speed while navigating through the waters north of the airport island. Data from the AFCD long-term studies (Hung 2012, 2013) and the intensive one-year study conducted for the 3RS EIA identify that such vessel movements caused intermittent behavioural changes in CWDs as they attempt to avoid rapid and noisy ferry approaches, especially while foraging or transiting across ferry lanes. However, the EIA recognised that the risks to CWDs decrease as vessel speeds are reduced and therefore, any reduction in speed from 30-40 knots will reduce potential adverse impacts on CWDs.

Based upon the newly constrained stretch of marine waters between the new HKIAAA and Sha Chau and Lung Kwu Chau Marine Park (SCLKCMP) that HSFs and CWDs would have to share, and the increased risk of collision leading to serious injury and mortality for the CWDs, the issue is considered a high impact and effective mitigation measures, as detailed in Section 2.3, will be needed.

The 3RS EIA described the data presented by Sims et al. (2012) show that the HSFs of Hong Kong release a lot of noise energy into the marine environment along their travel route, with a ferry approaching at a speed greater than 20 knots at 166 m distance from the hydrophones, resulting in an overall sound pressure level of around 120 dB re. 1 ųPa, with levels still being as high as 100-105 dB at a distance of 565m, in the CWD communication range of about 3 kHz and higher. CWD sounds have been measured as about 168 dB re. 1ųPa at their source (Li et al. 2012), 1 m distance from the CWD’s head, and since their sounds attenuate strongly with distance, there is a potential that fast ferries mask or restrict the range of CWD communications. It was hence concluded that the noise impacts from SkyPier HSFs on CWDs is considered to be of moderate impact significance during construction phase and of moderate-high impact significance during operation phase, requiring mitigation as detailed in Section 2.3.

The effects of vessel traffic on cetaceans around the world have been well documented in the past. Behavioural changes such as spatial avoidance, increase in swimming speed, changes in diving behaviour and acoustic behaviour, which could be regarded as impact, have been studied extensively in various studies (Hung, 2012). While the general idea that vessel noise affects cetaceans is well-established (Jensen et al., 2009), there is currently no published study which has investigated the impact of noise level and speed of HSF specifically on CWD behaviour. However, a number of studies as discussed below identifies that speed reduction of HSF can reduce the underwater noise level generated, and subsequently the impact on CWD communication and behaviour is anticipated to be lessened.

A recent study measured the underwater radiated noise from a high-speed jet propelled watercraft while the vessel passed at speeds of 12, 24 and 37 knots (Rudd et al., 2014). The broadband (0-22kHz) sound pressure levels of the ship at all directions (i.e. bow aspect, broadside aspect and stern aspect) decreased up to 20dB, when the speed was reduced from 37 knots to 12 knots. Evidence from the passive acoustic monitors termed Ecological Acoustic Recorders (EAR) data collected during the 3RS EIA shows comparable information. High speed ferries were tracked by the land-based theodolite station at the northeast of the HKIA, with the underwater sound simultaneously recorded by the nearest EAR Station at approximately 500 m from the existing HSF route. Sound pressure levels in the 4-8 kHz octave band (important for CWD whistle communication) proportional to HSFs speed were recorded, with each sound level calculated as a mean from 5 ferries per speed category from 6-8 knots to 26-30 knots (see Table 2‑2 ). A reduction of about 60% underwater sound energy in the CWD whistle communication frequency were found by comparing of the measurement results of 26-30 knots HSF speed and that of 15 knots, and similar underwater noise reduction will be expected by slowing the HSFs from 30-40 knots to 15 knots. Therefore both literature and field data show that slowing the HSFs from 30-40 knots to 15 knots will substantially reduce the noise levels approximately by 60% underwater sound energy or 4dB so as to alleviate the acoustic disturbance to the CWDs.

Table 2‑2 Speed of High Speed Ferry and the Corresponding Sound Pressure Level

|

Speed of HSF (knots) |

Sound Pressure Level (dB)* |

|

6-8 |

97 |

|

11-20 |

99 |

|

21-25 |

100 |

|

26-30 |

103 |

* sound pressure levels in the

4-8 kHz octave band at an average distance of 500 m from the EAR station

A Cumulative Effects Assessment (CEA) taking

data from 1996 to 2013 conducted by Marcotte et al. (2015) indicated a long-term effect of HSF

traffic on CWD travelling behaviour and distribution, as operation of SkyPier HSFs was linked by these authors to reduced dolphin

occurrence especially in the Brothers Islands area to the east of the existing

airport, and at the same time the dolphin density within SCLKCMP increased.

An Australian study revealed the indirect impact of transiting boat traffic (i.e. the boats which travelled through the CWD habitat without approaching the dolphins for the purpose of viewing them) on the acoustic behaviour of CWDs (Van Parijs and Corkeron, 2001). The boats’ passage did not affect the rates at which CWDs produced click trains and burst pulse vocalizations, however, CWDs significantly increased their whistling rate immediately after a boat had passed through but was still within 1.5 km from the CWD groups. The study suggested that the noise from transiting vessels affected the CWD group cohesion, and the dolphins need to re-establish vocal contact with associates after the masking noise of the vessel had passed. In particular, mother-calf pairs produced the highest whistle rate, probably demonstrating their greater need to reassure each other of their presence. With the attenuation in noise levels associated with HSF speed reduction, it is anticipated that due to the reduction on underwater noise energy generated, the impact on CWD communication would be diminished, and the dolphins probably would not need to expend as much energy in adjusting the timing of their signals.

In addition, underwater noise shifts in

loudness and pitch attendant with vessel speed changes present a

particularly-strong disturbance as gear shifts are found to produce broadband

(0 -35 kHz) and high-level sound (peak-peak source levels of up to 200 dB re

1μPa) of high amplitude, short-duration and reverberant nature, which is

much higher than regular engine noise (around 90-130dB re 1μPa) (Jensen et

al. 2009). Therefore, rapid and frequent speed changes should be avoided to

reduce both disturbance to CWDs and also potential vessel/CWD collisions. The

simple change in speeds (change in "closing-in distance") may also

present an extra physical danger to marine mammals because of the added

unpredictability of where the boat will be relative to the animals (Rudd et al.

2014). In other words, it is likely that dolphins can anticipate the imminent

arrival of a vessel from the approaching noise (Scheer

and Ritter 2013), but would be confused as to anticipation of when the boat

would be above or near them by a sudden change in boat speed (see also Würsig and Evans, 2001 for a general discussion of boat

operations near cetaceans).

In view of the moderate to high indirect

impacts to CWDs resulting from HSFs (see Table 2‑1),

mitigation measures in relation to marine traffic control need to be specified

to reduce acoustic disturbance, risk of injury or mortality and changes to

abundance and patterns of habitat use. Once the project construction is

underway, the paths of vessel movements from the east side of the airport

platform to the waters west of Hong Kong will be further restricted. The EIA

Report identified that having an increasing number of high-speed vessels, using

a narrower corridor of movement, results in closer spacing of the vessels and

less area for CWDs to surface without increased risk of being hit by a vessel

and exposure to higher levels of anthropogenic noise, this known to cause

behavioural disturbance to dolphins.

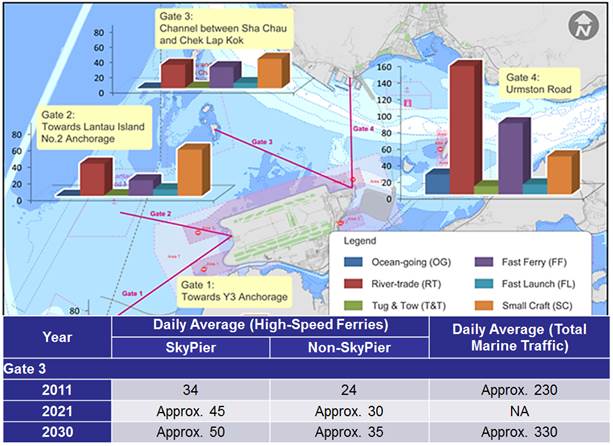

In the approved EIA report, route diversions to the north of SCLKCMP for SkyPier HSFs operating to / from Zhuhai and Macau were

proposed to mitigate the potential impacts on CWDs resulting from HSFs using a

narrower navigation corridor between SCLKCMP and the new 3RS land formation. It

is anticipated that HSFs using a narrower corridor would result in closer

spacing of the vessels and a reduced area for CWDs to surface leading to

increasing risk of being hit by HSFs and disturbance from increased

anthropogenic noise. For the section of diverted route passing through high CWD

abundance grid squares, a 15-knot speed controlled zone is proposed to reduce

potential adverse impacts on CWDs within these areas. The reduction in speed to

15 knots is expected to reduce collision risk and result in less acoustic and

behavioural disturbance to CWDs. During simulations of the HSF route diversion

(e.g. a Full Bridge Simulation Workshop was undertaken) it was determined that

HSFs can operate much more reliably at 15 knots rather than at 10 knots in the

vicinity of the proposed speed controlled zone. It

was also found that HSFs operating at 10 knots for a long distance would be

more likely to cause sea sickness, especially under choppy sea conditions. Therefore,

the 15 knots speed restriction was determined to be optimal with an acceptable

reduction in risk to CWDs.

Before the end of 2015 it is proposed that SkyPier

HSFs operating to / from Zhuhai and Macau would divert north of the SCLKCMP

with a 15 knot speed limit to apply for the part-journey crossing high CWD

abundance grid squares. This mitigation is considered effective as it will be

adopted by all SkyPier HSFs operating to / from

Zhuhai and Macau (constituting up to 60% of the HSFs in this area) and it would

avoid the current situation of the SkyPier HSFs

travelling to Zhuhai and Macau passing south of the SCLKCMP at high speeds

thereby substantially reducing the impacts of these vessels in this area Figure

2‑1.

Figure 2‑1 Marine Traffic Forecast of HSFs Navigating between HKIA Approach Area and South of the SCLKCMP

Source: Extracted from 3RS EIA Report – Table 13-27; Appendix 13.13 Figure 1b and Table 2

It is also noteworthy that the SCLKC North diverted route is expected to result in less impact on CWD travelling areas, as the stretch of navigation waters for the diverted route going via SCLKC north is much wider (approx. 2.4km) than that of the existing route along the airport north (approx. 0.6km) (See Figure 2‑2). SkyPier HSFs using the diverted route going via SCLKC north will have less conflict with the CWD travelling area and hence less risk of collision with CWD. The diverted route via SCLKC north will also reduce the SkyPier HSF travel time across the “Core Area” of the Pearl River Estuary (PRE) CWD National Nature Reserve (see Figure 2‑3).

Figure 2‑2 Stretch of Navigation Waters for the Diverted Route to SCLKC North and the Existing Route along Airport North

Figure 2‑3 Recommended Route Diversion and the PRE CWD National Nature Reserve

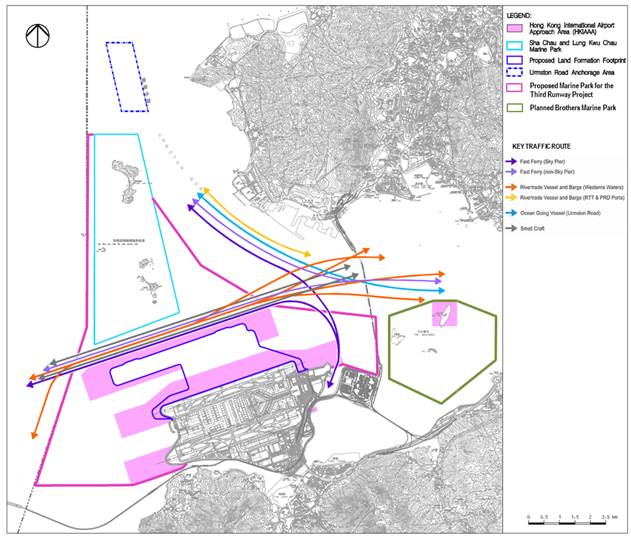

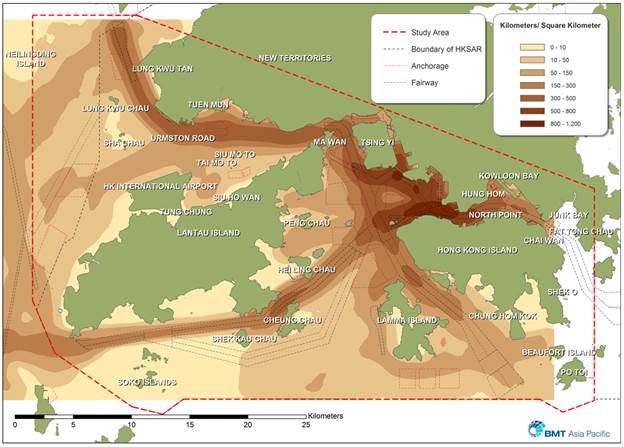

The number of SkyPier HSFs using the existing route was 34 in 2011 and projected to increase to approx. 50 in 2030 compared to approx. 540 total vessels using Urmston Road in 2011 and projected to increase to approx. 810 in 2030 (see Table 2‑3) (i.e. about 6% of the total marine traffic in Urmston Road). While the additional diverted traffic (typically 1 – 4 movements per hour during SkyPier HSF operating hours) does make Urmston Road marginally busier, the number of additional vessels is not significant compared to the total marine traffic in Urmston Road and is not anticipated to result in any congestion problem. Even with the proposed SkyPier (Macau / Zhuhai) HSF route diversion, the marine traffic density in Urmston Road in the future would remain lower than the marine traffic density in certain other Hong Kong shipping channels, for example in the Western Harbour where marine traffic density is higher (see Figure 3‑2). It is noted that even these busy areas of Hong Kong waters do not experience significant congestion issues, it is therefore summarised that the proposed SkyPier (Macau / Zhuhai) HSF route diversion will not lead to any significant added congestion in Urmston Road. In addition, the diverted route of SkyPier HSF will be along the western part of Urmston Road and will therefore avoid overlapping with majority of the existing marine traffic along the eastern part of Urmston Road.

Table 2‑3 Daily Average of High-Speed Ferries and Total Maine Traffic in Year 2011 and Projection to Year 2030:

|

Year |

Daily Average (High-Speed Ferries) |

Daily Average (Total Marine Traffic) |

|

|

SkyPier |

Non-SkyPier |

||

|

(i) via South Sha Chau |

|||

|

2011 |

34 |

24 |

Approx. 230 |

|

2021 |

Approx. 45 |

Approx. 30 |

NA |

|

2030 |

Approx. 50 |

Approx. 35 |

Approx. 330 |

|

(ii) via Urmston Road |

|||

|

2011 |

54 |

54 |

Approx. 540 |

|

2021 |

Approx. 70 |

Approx. 70 |

NA |

|

2030 |

Approx. 80 |

Approx. 80 |

Approx. 810 |

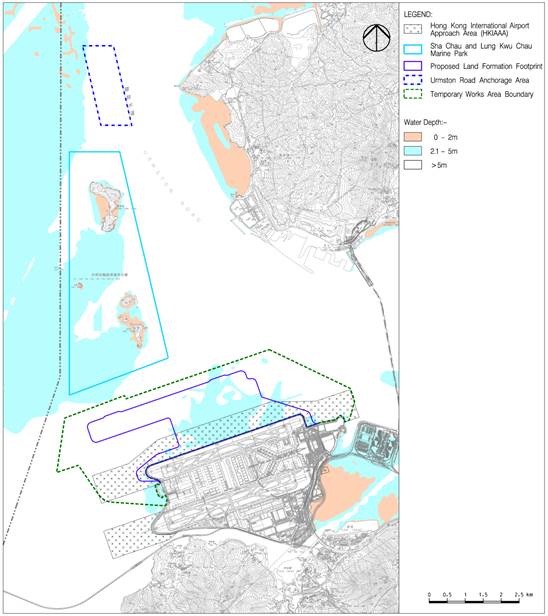

It is

considered unsafe for HSFs (with a draft of approximately 1 - 2m) to travel in

shallow water zones where water depth is less than 2m. The western and

northwestern waters of Urmston Road Anchorage Area contain several shallow

water zones with general water depth of less than 2 m (see Figure 3‑1).

Therefore, the diverted route of HSFs should avoid those areas due to safety

concerns.

Figure 3‑1 Various Marine Constraints in the North Lantau Waters

There are restricted areas in the vicinity of Hong Kong International

Airport (i.e. HKIAAA) where vessels are not allowed to pass through without

authorization. The diverted route shall avoid the HKIAAA as shown in Figure

3‑1.

The local constraints imposed by the

works area of the 3RS project or adjacent projects (e.g. the Hong

Kong-Zhuhai-Macao-Bridge HKBCF/ Tuen Mun-Chek Lap Kok Link (TM-CLKL)),

SCLKCMP, and other marine facilities such as the Urmston

Road Anchorage (see Figure 3‑1)

shall also be considered in designing marine travel routes for SkyPier HSFs.

The proposed temporary works area of the 3RS project will be demarcated

by floating booms, and the route of HSFs need to be

designed to avoid entering any construction works area for safety reasons.

According to the Marine Parks Ordinance (Cap.476) and the Marine Parks and Marine Reserves Regulation (Cap.

476A), any operating vessels are

not allowed to travel at speed exceeding 10 knots inside Marine Park. Besides, to minimise

disturbance to the SCLKCMP, the route alignment of SkyPier

HSFs shall avoid the Marine Park.

For the Urmston

Road Anchorage, in view of the marine vessels that may anchor at this area, it

is proposed to avoid routing the diverted route through this area due to safety

concerns and potential operational impacts.

Areas with high CWD abundance (e.g. in and around

Sha Chau and Lung Kwu Chau Marine Park) form another constraint to be considered during the design of the marine traffic route. As discussed

in the sections above, other issues such as water depth, HKIAAA and other facilities are absolute constraints that have to be

avoided due to safety concerns and potential operational impacts. However it is

feasible for the diverted route to pass through areas with high CWD abundance

provided that there is suitable mitigation measure (i.e. speed reduction) to

minimise the impact of the HSFs on CWDs in these areas. In Section 3.3, a

dolphin habitat rating system is

developed based on recent data for designation of

speed controlled zone along the proposed diverted route, which can reduce the

impact on CWDs. With the provision of proper training to HSF captains that they

can strictly follow the pre-defined travel route (see Section

4.4.1)

The disturbance to dolphins (which would presumably adapt to the predictable

routes) due to vessel movements would be reduced.

The design of proposed marine travel

route for SkyPier HSFs has taken into account the

various marine constraints as discussed in Section

3.1.

The captain shall strictly follow all navigation safety requirements

(e.g. local regulations

and requirements of the Marine Department) and

relevant international practices. The marine travel route will be fine-tuned

locally for safety

reasons, taking into account other marine vessels that may be encountered. For

instance, at Urmston Road where the traffic density

is relatively high (see Figure

3-2), sudden sharp angle turning with high speed is not encouraged. The

navigation route may also be affected by natural conditions such as wind, current,

wave, poor visibility, extreme weather event etc.; special events such as

closure of routes due to fireworks and other events; and avoidance of shallow

water areas and stranded ships.

Figure 3‑2 Existing Marine Traffic Plan

(BMT, 2014)

Note: The unit Kilometers / Square Kilometer describes the total length

of vessel routes within each square kilometer.

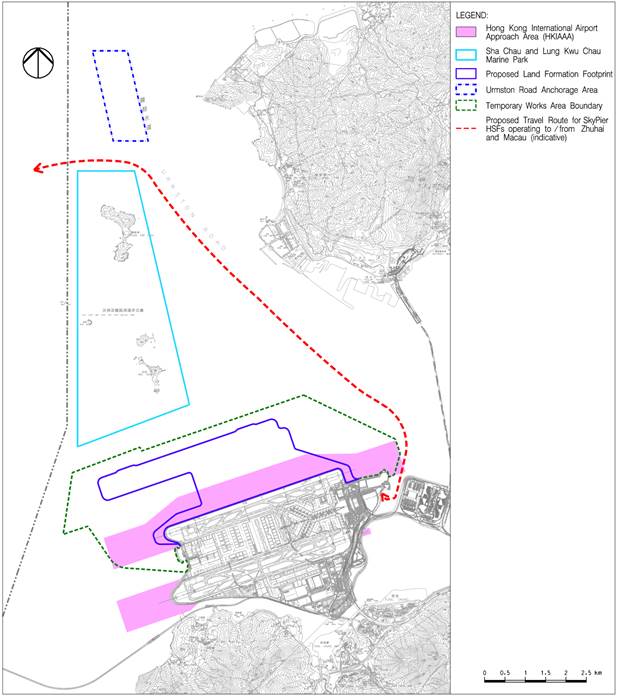

An indicative diverted marine travel

route for HSFs travelling between SkyPier and Zhuhai

or Macau is shown in Figure 3‑3.

Upon leaving or arriving at SkyPier, the HSFs have to

make a slight detour around the HKIAAA and temporary works area of the 3RS

project. For the water space between HKIA and Pillar Point/ Castle Peak Power

Station, sharp angle turning in high speed is avoided in Urmston

Road due to safety navigation issues. In order to avoid going through the Urmston Road Anchorage and SCLKCMP, the proposed route has

to pass through the channel between these two areas. As discussed in Section

3.1.1, it is not feasible to divert the route to north of Urmston Road Anchorage as the HSFs then have to transit

through northwest and west of the Urmston Road

Anchorage, which are shallow water zones with general water depth less than 2

m. Doing so would be unsafe.

Figure 3‑3 Pre-defined Marine Travel Route for SkyPier HSFs operating to / from Zhuhai and Macau

In order to determine the area to which HSF

speed limits should be applied for reducing impacts on CWDs, data from the AFCD

long-term surveys (see Hung 2014 for a description of these data) have been

evaluated to make the best possible determination of the relative value of each

1 x 1 km grid for use in this exercise. The latest available data including the

recent marine mammal monitoring report (Hung, 2015) has been taken into account

for developing the dolphin habitat index.

It was decided that, in order to avoid

potential biases from any single measure, a matrix of four measures of dolphin

use of each grid would be used. For each 1 x 1 km grid in the potential HSF

route area, four factors have been considered:

1)

Current

density by DPSE, i.e. the number of CWDs per 100 units of survey effort in the

1 x 1 km grid (Figure

3‑4;

from Hung 2015)

2)

Historical

density by DPSE (Figure

3‑5;

from Hung 2014)

3)

Habitat

rating (Figure

3‑6;

from Hung 2014)

4)

50%

core area usage by CWDs (Figure

3‑7;

from Hung 2014)

All of these four factors are based on

dolphin numbers per unit effort, but including data on the four factors helps

to ensure the analysis has broad temporal and biological relevance, and

minimizes impacts of potential data anomalies from using just a single factor.

A matrix of the relevant data was compiled. For each 1 x 1 km grid, there are

four values presented, corresponding to the four factors listed above, and for

each one evaluated as “Low”, “Medium” or “High” (note that these are subjective

descriptive terms, though objective quantitative values for building the matrix

were used). For densities (both current and historical), the corresponding

values for “Low” were 0.0-20.0, 20.1-40.0 for “Medium”, and 40.1 or above for

“High”. For habitat ratings, the corresponding values for “Low” were 0-10,

11-20 for “Medium”, and 21 or above for “High”.

For 50% core areas, the corresponding values for “Low” were 0-10, 11-30

for “Medium”, and 31 or above for “High”. Relevant raw data are presented in

detail in Hung (2014) and Hung (2015). The dolphin habitat index is then

developed for each grid as shown in Table 3‑1.

Table 3‑1 Criteria for each 1 km2 grid in defining the dolphin habitat index, based on the ranking of four factors (i.e. current density by DPSE, historical density by DPSE, habitat rating and 50% core area usage by CWDs)

|

Dolphin habitat index |

Criteria |

|

Least

Critical |

·

3

“Low”; or ·

4

“Low” |

|

Less

Critical |

·

2

“Medium” and 2 “Low”; or ·

1

“High” and 1 “Medium” and 2 “Low” |

|

Moderately

Critical |

·

2

“High” and 1 “Medium”; or ·

2

“High” and 2 “Low”; or ·

1

“High” and 2 “Medium”; or ·

3

“Medium” |

|

Highly

Critical |

·

3

“High”; or ·

4

“High” |

The resulting matrix (see Figure

3‑8)

demonstrates a highly critical CWD habitat to the northeast of SCLKCMP. It is

well-known that HSFs can adversely impact cetaceans, both by behavioral disturbance and ship strikes (see Van Waerebeek et al. 2007, Ritter 2010, Carrillo and Ritter

2010). SkyPier

ferries can significantly reduce impacts on dolphins by slowing to 15 knots in

this section of important dolphin habitat extending all the way to the HK/PRC

boundary.

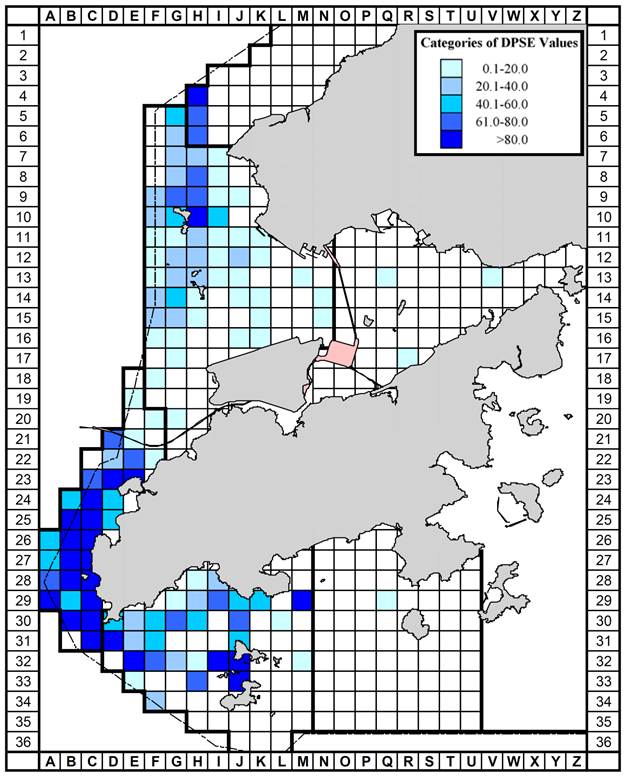

Figure 3‑4 Current density of Chinese White Dolphins with corrected survey effort per km2 in waters around Lantau Island between January – December 2014 (number within grids represent “DPSE” = no. of dolphins per 100 units of survey effort; from Hung, 2015). In the dolphin habitat index developed for this plan, DPSE of 0.0 – 20.0 is rated as “Low”, 20.1 – 40.0 as “Medium” and 40.1 or above as “High”.

Figure 3‑5 Historical density of Chinese White Dolphins with correct survey effort per km2 in waters around Lantau Island during 2001 – 2012 (numbers within grids represent “DPSE” = no. of dolphins per 100 units of survey effort; from Hung, 2014). In the dolphin habitat index developed for this plan, DPSE of 0.0 – 20.0 is rated as “Low”, 20.1 – 40.0 as “Medium” and 40.1 or above as “High”

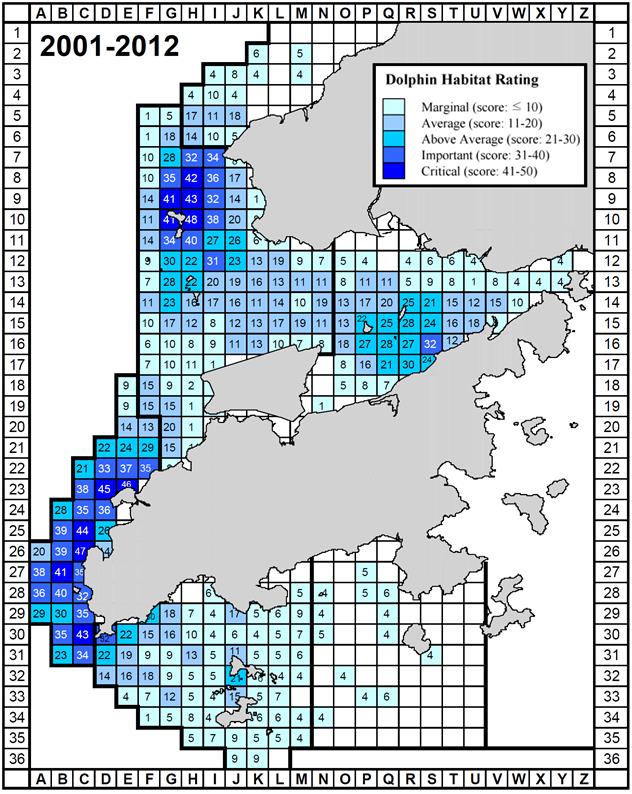

Figure 3‑6 Habitat rating of Chinese White Dolphins in Hong Kong using quantitative habitat use information collected during 2001 – 2012 (number with grids represents the sum of scores totalled from 10 selection criteria; from Hung, 2014). In the dolphin habitat index developed for this plan, habitat rating of 0 – 10 is rated as “Low”, 11 – 20 as “Medium”, and 21 or above as “High”

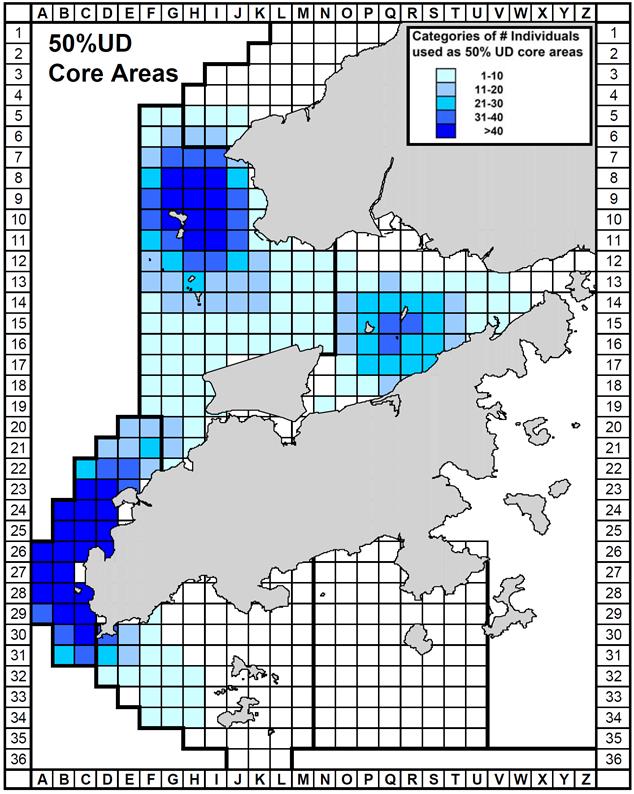

Figure 3‑7 Number of individual Chinese White Dolphins with their 50% utilization distribution (UD) core areas overlapped with each 1 km2 grid in waters around Lantau Island from 2001 – 2012 (Hung, 2014). In the dolphin habitat index developed for this plan, 50% core area of 0-10 is rated as “Low”, 11-30 as “Medium”, and 31 or above as “High”

Figure 3‑8 Dolphin Habitat Index Developed for this Plan

The indicative diverted marine travel route in Section 3.2 is overlaid with the Dolphin Habitat Index developed in Section 3.3 to determine the location of speed controlled zone (SCZ) along the route. The proposed marine travel route together with the 15-knot SCZ is shown in Figure 3‑9.

Figure 3‑9 Speed Controlled Zone for SkyPier HSFs

As illustrated in Figure 3‑9, for the waterspace between HKIA and Pillar Point/ Castle Peak Power Station, the route shall mainly transit through the “Least Critical” dolphin habitat grids. When leaving and/ or approaching the SkyPier terminal at the HKIA, ferries should gradually increase and/ or decrease speed. On approaching the “Highly Critical” dolphin habitat grids around SCLKCMP, they are required to enter a defined 15-knot SCZ at the north and northeast of SCLKCMP. They are required to enter and/ or leave the SCZ through Gates A-B-C and E-F (see Figure 3‑9), hence their movement through the “Highly Critical” dolphin habitat is restricted, which would minimise their chances of encounter with CWDs (and may allow dolphins to habituate to these predictable routes). When travelling through the SCZ, they must adhere to the speed limit of 15 knots, and as such they have to decelerate gradually before entering the SCZ, and can only increase the speed to over 15 knots upon leaving the SCZ gradually to avoid rapid speed changes. As mentioned in Section 2.2.3, rapid and frequent speed changes should be avoided to reduce both disturbance to CWDs and also potential vessel / CWD collisions, and it will be communicated to HSF captains during the skipper training workshops that they need to reduce speed gradually reaching 15 knots or less before entering the SCZ, and increase speed gradually also upon leaving the SCZ. Should the SkyPier HSFs that use the Urmston Road to travel north into the PRE also interface with the speed restriction area for the SkyPier HSFs operating to / from Zhuhai and Macau, then they would also be required to adhere to the 15 knot speed restriction.

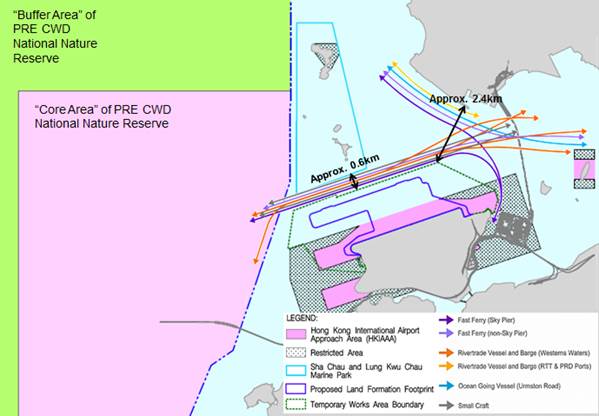

The CWD density

grids from the Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macao Bridge Hong Kong Link Road Environmental

Monitoring & Audit (EM&A) reports have also been

reviewed. As these data only cover short survey periods and there is no annual

data available, they were not used in the establishment of the habitat rating

index in Section 3.3.

However, these data provide further support on the design of the marine travel

route and SCZ. Results of EM&A reports show that all grids with high CWD

density pass through by the proposed travel

route are covered by the proposed 15-knot SCZ.

Besides, the section of marine travel route with no speed restriction generally

crosses grids with no or low CWD density (see Figure

3‑10).

The latest CWD data from HZMB EM&A are consistent with the habitat rating

index and support the design of the marine travel route and 15-knot SCZ.

Figure 3‑10 Density of Chinese white dolphins from HZMB-HKLR Monitoring Reports

The EIA projected continued growth in SkyPier HSF traffic up to 2030 (to approximately 130 annual average daily HSF movements) and impact assessments were based on these increasing traffic levels. Even taking into account traffic growth, the EIA determined that the route diversion and speed controlled zone proposed would be able to reduce impacts from HSFs to acceptable levels in affected marine waters. Further to receiving feedback on this aspect during the EIA public comment period, AAHK has committed to an additional precautionary measure of capping SkyPier HSF movements based on historic operations data (i.e. an annual daily average of 99 movements), this to be effective in the period before designation of the proposed marine park.

During the main ACE and ACE EIA Sub-committee discussions on the 3RS EIA, members also recommended that AAHK should further explore the feasibility of imposing a maximum daily cap on the number of HSF leaving the SkyPier and imposing further speed restrictions at different spots along the diverted marine route after detailed study. Although the EP specifies exploring the feasibility of the daily cap for HSFs leaving the SkyPier, the annual daily average cap of 99 and the maximum daily cap being proposed in this plan refer to HSF movements at SkyPier. One movement comprises a SkyPier departure or an arrival.

As required in the EP, AAHK will cap

the SkyPier HSF movements at an annual daily average

of 99 prior to designation of the proposed marine park in addition to the route

diversion and speed restrictions in high-density CWD areas. The commitment to

an annual daily average of 99 SkyPier HSF movements

has taken into account a number of operational considerations, for example

expected seasonal fluctuations above and below the annual daily average and to

allow some capacity for operations recovery after inclement weather events

(e.g. typhoons) and expected peak demand periods during any year, for example

Lunar New Year or the Golden Week holiday when very high traffic demand is

expected. A further maximum daily movement cap has been explored. It is recognised that imposing an absolute cap on maximum daily

movements at SkyPier may present a significant

operational challenge in particular during busy periods each year for example

the golden week holiday or to accommodate HSF service recovery in the aftermath

of inclement weather events. In order to establish a reasonable maximum daily

capping commitment, scheduled and actual HSF movements at SkyPier

since 2010 have been reviewed.

The history of SkyPier

HSF movements since 2010 shows that actual daily HSF movements only vary up and

down slightly (within +/- 5 movements) from the annual average daily movements

for the vast majority of days in any year. Yet there are rare occasions over

this period when larger fluctuations have been experienced and these had to be

handled. During this period the highest number of scheduled movements in any

one day was 123, although actual movements on the day in question were a little

below this. Over the period since 2010, days with HSF movements above 110

totalled less than 30. Thus, in order to allow similar levels of flexibility

for SkyPier HSF operators as has previously been

possible it is proposed to adopt 125 movements as the maximum daily movement

cap in conjunction with the overall commitment to 99 annual daily average HSF

movements. Setting this target will provide operational flexibility for

handling any unexpected and rare operational challenges. It is again stressed

that the proposal for a maximum daily cap of 125 movements does not alter the

main commitment to 99 annual daily average HSF movements.

In order to ensure that the annual

daily average HSF movements can be kept within the target of 99 per day – or

36,135 movements during one whole year (with 365 calendar days) - AAHK intends

to work closely with SkyPier HSF Operators to ensure

that during ‘normal’ operations, daily movements are slightly below the 99

target such that a buffer of extra movement slots develops that balances both

the expected days when several extra movements above the 99 target will be

experienced and to offset the very rare peak service days when more than 110

movements may need to be handled by HSF operators.

The annual daily average limit and

the maximum daily movement cap would be implemented before the end of 2015 and

will be in effect during the period before designation of the proposed Marine

Park.

The current route diversions and speed controlled zones as proposed in this plan represent the full extent of the proposed route diversion and speed control mitigation measures. With the proposed route diversion, the SkyPier HSFs are prohibited from entering the Marine Prohibited Zone as defined in Figure 3‑11. This Marine Prohibited Zone is developed based on the dolphin protection area proposed during the construction phase in response to the ACE comments, within which there is stringent management control on SkyPier HSFs. This Marine Prohibited Zone covers much of the “Moderately Critical” and “Highly Critical” dolphin habitats that are in the vicinity of the proposed route alignment for diverted HSFs, and hence serve to protect these areas from disturbances by the HSFs.

The route alignment for diverted HSFs within Hong Kong boundary will not encounter “Highly Critical” dolphin habitat grids except inside the SCZ as proposed in Section 3.4 where a 15-knot speed restriction shall apply (most of the remaining diverted route falls in least or less critical dolphin habitat index areas). It has been established through both literature review and field data that slowing HSFs from 30-40 knots to 15 knots can substantially reduce the noise levels by approximately 60% (underwater sound energy) or 4dB thereby alleviating acoustic disturbance to CWDs. However, gear shifts are found to produce broadband (0-35 kHz) and high-level sound (peak-peak source levels of up to 200 dB re 1μPa) of high-amplitude, short-duration and reverberant nature, and as such it is recommended that frequent and rapid HSF speed changes (requiring gear shifts) should be avoided if possible. When entering and leaving the SCZ, it is recommended that HSFs should reduce speed gradually to 15 knots or less before entering the SCZ, increasing speed gradually on leaving the SCZ. Because frequent speed changes with more gear shifts can result in higher disturbance to CWDs, the imposition of further speed restrictions on any additional sections along the pre-defined travel route between SkyPier and the entrance gate to the SCZ may be counterproductive, The gradual deceleration of HSFs before entering the SCZ and gradual acceleration after leaving the SCZ is expected to be effective in further minimising disturbance to CWDs and hence further speed restriction zones along the relatively short travel route between SkyPier and the SCZ are not recommended.

With

the precautionary measures as described in Section 4.3

in place, potential impacts of SkyPier HSFs on

CWDs could be further reduced.

It is recognised

that the density and hence the habitat index of CWDs is dynamic and will change

over time. As 3RS marine construction

works are expected to be underway for a number of years, it is proposed that

the Environmental Team shall review the density and habitat index from time to

time during the construction period and make suggestions on appropriate changes

/ alterations to what is defined in this plan based on identified changes (for

example to be adopted in new agreements with Ferry Operators using SkyPier.

In the operation phase, any decision

on the section of the diverted route subject to the speed limit and its

application to SkyPier ferries will be taken after

consideration of updated CWD abundance data from both the AFCD database and

from additional 3RS EM&A data obtained during the pre-construction and

construction monitoring periods. Of particular importance to this decision will

be the updated information available at that time on CWD abundance in Hong

Kong. Besides,

after successful designation of the proposed Marine Park, all vessels will be

required to travel with a speed limit of 10 knots within the proposed Marine

Parks according to the Marine Park Ordinance.

Figure 3‑11 Marine Prohibited Zone for SkyPier HSFs

The recommended route diversion and

15-knot speed control for SkyPier HSFs travelling to/

from Zhuhai and Macau is intended to alleviate the otherwise moderate to high

impacts on CWDs that would be caused by HSFs navigating in the narrower waters

between the north of HKIA Approach Area and the south of SCLKCMP that result

from the 3RS land formation . In particular, the aim of setting the 15-knot

speed control zone is to alleviate the CWD impacts due to additional marine

traffic caused by the diverted SkyPier HSFs going

through the CWD travel area located to the north of SCLKCMP. Therefore, the

15-knot speed control will not apply to the existing SkyPier

HSFs heading north to the Pearl River Delta (PRD).

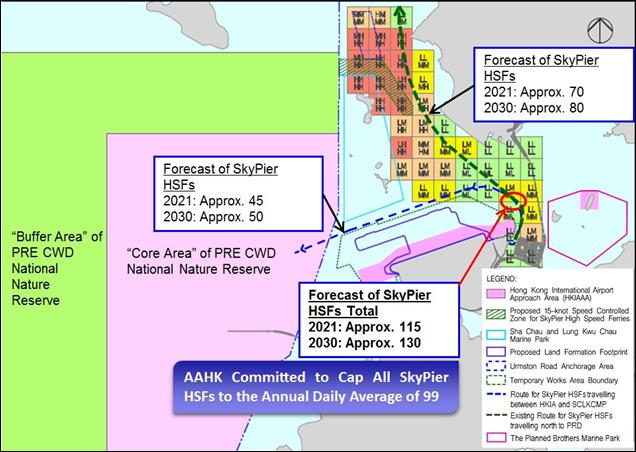

As detailed in Figure 1b and Table 2

of Appendix 13.13 of the EIA Report, it is projected that the total number of SkyPier HSFs would increase from the current annual average

daily traffic level of less than 100 to about 130 in 2030 (see Figure 3‑12).

As a precautionary measure to further reduce the potential impacts on CWD due

to HSFs travelling in North Lantau waters, in addition to the EIA

recommendations, AAHK has committed to cap the SkyPier

HSF movements at an annual daily average of 99 (or 36,135 movements during one

whole year with 365 days) prior to designation of the proposed marine park -

the capped daily average of 99 covering all SkyPier

HSFs, including the diverted HSFs going to the west as well as the remaining SkyPier HSFs that are heading north into the PRD.

In addition, as per the

collective views on the SkyPier Plan from ACE, for

the SkyPier HSFs heading north to the PRD, AAHK shall

include the 15-knot speed requirement (when travelling across CWD hotspots in

Hong Kong) as one of the contract terms when tendering for the next SkyPier operation contract.

Figure 3‑12 EIA Forecast of Daily Average SkyPier HSFs in 2021 and 2030

Source: Figure 1b and Table 2 in Appendix 13.13 of the 3RS EIA

The

proposed route diversions and speed controlled zones will be implemented by

AAHK and the SkyPier Ferry Operators (FOs) by the end

of 2015. SkyPier HSFs will continue to use the route

diversion and speed control zone during both construction and operation phases.

The FOs will be required to track compliance regularly and this will be

specified in the supplemental agreement to ensure FOs follow all agreed restrictions.

In the operation phase, any decision on the section of the diverted route

subject to the speed limit and its application to SkyPier

ferries will be taken after consideration of updated CWD abundance data from

both the AFCD database and from additional 3RS EM&A data obtained during

the pre-construction and construction monitoring periods. Of particular

importance to this decision will be the updated information available at that

time on CWD abundance in Hong Kong.

In addition, AAHK and the SkyPier FOs will cap the number of SkyPier HSF at an annual daily average of 99 prior to designation of the proposed marine park.

The requirements in Section 3 will be specified in a ‘supplemental agreement’ with the Ferry Handling Agent for all SkyPier FOs. The following management commitments and requirements that are relevant to the implementation of the proposed route diversion and speed control section shall be stipulated in the supplemental agreements to the existing Ferry Operator agreements and will be included in future FO agreements:

§ All HSFs using the diverted route

shall install and operate GPS receivers / AIS transponders to facilitate

accurate route tracking and record keeping;

§ Ferry Operators shall provide information on the

number and type of ferry taking the diverted route for AAHK to verify on a

monthly basis;

§ Any non-compliance with the requirements and arrangements for diversion

and speed control shall initially result in warnings to operators, with any

repeated non-compliance leading to suspension of that

particular movement until submission of report explaining the reason of

non-compliance with preventive measures in place to the satisfaction of the

AAHK.

§ Vessel captain may decide to deviate from the proposed route in response

to an emergency or in the interest of public safety, e.g. in case of adverse

sea conditions. The ferry operators have to provide valid reasons to AAHK for

such case or otherwise the non-compliance shall lead to warnings or suspension

as indicated above.

The ET will audit various parameters

including actual daily numbers of HSFs, compliance with the 15-knot speed limit

in the speed control zone and diversion compliance for SkyPier

HSFs operating to / from Zhuhai and Macau

in accordance with this Plan and the 3RS EM&A Manual. The audit

outcome will be summarised in the monthly EM&A reports.

In addition, all ferry operators

shall comply with the relevant international conventions, and local regulations

and requirements of the Marine Department, including but not limited to the

following:

§ Merchant Shipping (Local Vessels) Ordinance, Cap

548 – This ordinance is related to the regulation and control of local vessels in

Hong Kong or in the waters of Hong Kong and for other matters affecting local

vessels, including their navigation and safety at the sea;

§ The International Regulations for Preventing

Collisions at Sea 1972 – This is an international regulation with rules

including safe speed, measures to identify collision risk, actions to avoid

collision and the actions to be taken during different situations to prevent

collisions;

§ The Shipping and Port Control Ordinance (Cap 313) –

This ordinance is related to the regulation and control of ports and vessels in

Hong Kong or in the waters of Hong Kong; and

§ The Shipping and Port Control Regulations (Cap

313A) – Rules for the navigation and control of vessels are presented in Part

III of this regulation.

Data from CWD monitoring by vessel surveys

will be used to monitor the effectiveness of the mitigation measures proposed

for the amelioration of impacts to CWDs. In addition, land-based CWD monitoring will be conducted at a location on

north Lung Kwu Chau to supplement the vessel

monitoring data in determining the effectiveness of the SkyPier

HSF route diversion and speed reduction in reducing disturbance to CWDs. Other

available land-based survey data collected near Lung Kwu

Tan and Urmston Road areas by other projects will also be reviewed to

supplement survey results. AAHK will report to ACE on the effectiveness of the

CWD mitigation measures six months after implementation of the SkyPier Plan, by reviewing and analysing data from CWD

monitoring surveys during the initial six month implementation of SkyPier HSF diversion and speed restriction.

Under the Marine Ecology and

Fisheries Enhancement Plan which was submitted to the

ACE in August 2014, AAHK proposed to fund and support initiatives in promoting

environmental education and eco-tourism in relation to the marine ecological

and fisheries resources in the North Lantau coast and Northwest Lantau waters.

One of the proposed initiatives was to develop and conduct skipper workshops to

alert HSF captains / drivers on the risk of collisions with CWDs and Finless

Porpoises, and ways of reducing such risks.

During the workshop, the following

information would be included:

· General education on local cetaceans;

· Guidelines for avoiding adverse water quality impact; and

·

Guidelines for operating vessels safely in the presence

of CWD.

In addition, several precautionary measures are recommended to HSF

operators for the route to / from Zhuhai and Macau:

· Ensure that all captains of HSF are well trained so that they can strictly follow the pre-defined travel route and speed restriction rules;

· The vessel captains should make sure that there is sufficient distance for slowing down prior to passing CWD hotspots and take action to avoid collision; and

· Vessel captains need to make sure that all reasonable efforts (within safety parameters) are taken to minimise the risk and disturbance to CWDs along the whole route, not just within the speed controlled zone.

This Plan has been developed pursuant to 3RS Project Environmental Permit (EP-489/2014) Clause 2.10 requirements. The 3RS Project EIA evaluated the impact of CWDs due to HSFs currently navigating in the waters between HKIAAA and SCLKCMP as moderate to high impact significance. A commitment was made that by the end of 2015, SkyPier HSFs operating to / from Zhuhai and Macau would divert north of SCLKCMP, with a 15 knot speed limit to apply for the part-journeys that cross high CWD abundance areas.

The design and alignment of the marine travel route for the diverting HSFs has taken into account a number of marine constraints. Recently available data from AFCD long-term surveys has been evaluated to determine a Dolphin Habitat Index (DHI) for North Lantau Waters, allowing further differentiation on the value of different habitat areas to CWDs. A speed limit of 15 knots is proposed for the section of the diverted marine travel route that corresponds with ‘highly critical’ dolphin habitat (i.e. a speed control zone). The recommended diversion of the SkyPier HSFs travelling to / from Zhuhai and Macau to the north of SCLKCMP is more preferable than the alternative routes towards the north boundary of HKIAAA due to less impact on CWD travelling area, less risk of collision with CWD at airport north waters and less impact on “Core Area” of PRE CWD National Nature Reserve.

AAHK is firmly committed to ensuring that an annual daily average of 99 SkyPier HSF movements is not exceeded prior to designation of the proposed Marine Park. AAHK will ensure that HSF movements are kept within the annual daily average target of 99 per day – or 36,135 movements during each year (with 365 calendar days). It should also be noted that the capped daily average of 99 covering all SkyPier HSFs, including the diverted HSFs going to the west as well as the remaining SkyPier HSFs that are heading north to PRD. Given the actual history of SkyPier HSF movements since 2010 and to provide reasonable operational flexibility for handling unexpected and rare operational challenges in future years, AAHK has proposed 125 as the maximum allowable movement number for any day, recognising that days with HSF movements of more than 110 totalled less than 30 since 2010. The annual daily average limit and the maximum daily movement cap would be implemented before the end of 2015 and will be in effect during the period before designation of the proposed Marine Park. The number of diverted SkyPier HSFs to Urmston Road would constitute only approximate 6% of the total daily marine traffic in Urmston Road, which is insignificant.

Additional

sections of speed control have been evaluated, however the remainder of the diverted

route alignment in Hong Kong waters falls largely in least or less critical DHI

areas and in these areas there is support that further HSF speed changes may

result in higher underwater noise impact / nuisance to CWDs; HSFs will however

be recommended to reduce speed / speed up gradually when entering / leaving the

speed control zone. The feasibility of imposing a speed limit to SkyPier HSFs heading north to the Pearl River Delta has

also been analysed. In

particular, the aim of setting the speed control zone is to alleviate the CWD

impact due to additional marine traffic caused by the diverted SkyPier HSFs that would travel through the important CWD

habitat. Therefore, the 15-knot speed control will not apply to the existing SkyPier HSFs heading north to the Pearl River Delta (PRD).

However, as per the collective views on the SkyPier

Plan from ACE, for the SkyPier HSFs heading north to

the PRD, AAHK shall include the 15-knot speed requirement (when travelling

across CWD hotspots in Hong Kong) as one of the contract terms when tendering

for the next SkyPier operation contract.

CWD monitoring by vessel surveys

supplemented with land-based surveys at Lung Kwu Chau

is proposed, to review the effectiveness of proposed mitigation measures on

CWDs. Regular audits shall be conducted by the Environmental Team and the

effectiveness of the mitigation measures on CWDs will be reviewed and reported

to ACE six months after implementation of the SkyPier

Plan.

Carrillo,

M and F. Ritter.

2010. Increasing numbers of ship strikes

in the Canary Islands: proposals for immediate action to reduce risk of

vessel-whale collisions. J. Cetacean Res. Manage. 11:131-138.

Hung, S. K. Y. (2012). Monitoring of marine mammals in Hong Kong waters (2011-12): Final report (1 April 2011 to 31 March 2012). Submitted to the Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department of the Hong Kong SAR Government. Retrieved from http://www.afcd.gov.hk/english/conservation/con_mar/con_mar_chi/con_mar_chi_chi/files/FinalReport2011to12pp1to120.pdf

Hung, S. K. Y. (2013). Monitoring of marine mammals in Hong Kong waters (2012-13): Final report (1 April 2012 to 31 March 2013). Submitted to the Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department of the Hong Kong SAR Government. Retrieved from http://www.afcd.gov.hk

Hung, S. K. Y.

(2014). Monitoring of marine mammals in

Hong Kong waters (2013-14): Final report (1 April 2013 to 31 March 2014). Submitted to the Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department

of the Hong Kong SAR Government. Retrieved from http://www.afcd.gov.hk

Hung, S. K. Y. (2015). Monitoring of marine mammals in Hong Kong waters (2013-14): Final report (1 April 2013 to 31 March 2015). Submitted to the Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department of the Hong Kong SAR Government. Retrieved from http://www.afcd.gov.hk

Jensen, F. H., Bejder, L., Wahlberg, M., Aguilar Soto, N., Johnson, M. & Madsen, P. T. (2009). Vessel noise effects on delphinid communication. Marine Ecology progress Series. 395:161-175.

Li, S., Wang, D.,

Wang, K., Taylor, E. A., Cros, E., Shi, W., Wang, Z.,

Fang, L., Chen, Y. & Kong, F. (2012). Evoked-potential audiogram of an

Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin (Sousa chinensis). Journal of Experimental Biology, 215,

3055-3063.

Marcotte, D., Hung, S. K. & Caquard,

S. (2015). Mapping cumulative impacts

on Hong Kong's pink dolphin population.

Ocean & Coastal

Management. 109: 51-63.

Marine Department (2013). PAC Paper No. 3/2013 - Pilotage Advisory Committee – Establishment of Principal Fairways in the Waters North of Lantau Island. Retrived from http://www.mardep.gov.hk/en/aboutus/pdf/pacp3_13.pdf

Ng, S. L. & Leung, S.

(2003). Behavioural response of Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin

(Sousa chinensis) to vessel traffic. Marine Environmental Research, 56, 555-567.

Piwetz, S., Hung, S., Wang, J.,

Lundquist, D. & Würsig, B. (2012). Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin (Sousa chinensis) movements off Lantau Island, Hong Kong:

Influences of vessel traffic. Aquatic Mammals, 38, 325-331.

Ritter, F. (2010). Quantification of ferry traffic in the Canary Islands (Spain) and its

implications for collisions with cetaceans. Journal of Cetacean

Research and Management, 11(2), 139-146.

Rudd, A. B., Richlen,

M. F., Stimpert, A. K. & Au, W. W. L. (2014). Underwater

sound measurements of a high speed jet-propelled marine craft: Implications for

large whales. Pacific Science "Early View".

69: pages to be assigned.

Scheer, M. & Ritter, F.

(2013). Underwater bow-radiated noise characteristics of three types of

ferries: Implications for vessel-whale collisions in the Canary Islands, Spain.

International Whaling Commision Report SC/65a?HIM01

Sims, P. Q., Hung, S. K. & Würsig, B. (2012). High-speed vessel noises in

West Hong Kong waters and their contributions relative to Indo-Pacific humpback

dolphins (Sousa chinensis). Journal of Marine

Biology, 2012, pp. 11.

Van

Parijs, S.M. and Corkeron,

P.J. (2001).

Boat traffic affects the acoustic

behaviour of Pacific humpback dolphins, Sousa chinensis.

Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 81: 533 –

538.

Van

Waerebeek, K, AN Baker, F Fernando, J Gedamke, M Iñiguez, GP Sanino, E Secchi, D Sutaria, A

van Helden, and Y Wang. 2007. Vessel collisions with small cetaceans

worldwide and with large whales in the southern hemisphere, an initial

assessment. Latin American Journal of Aquatic Mammals 6:43-69.

Würsig,

B. & Evans, P.G.H. 2001. Cetaceans

and humans: Influence of noise. IN: Marine Mammals: Biology and

Conservation, ed. by P.G.H. Evans and J.A. Raga. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Press,

NY.